Types of childhood cancer

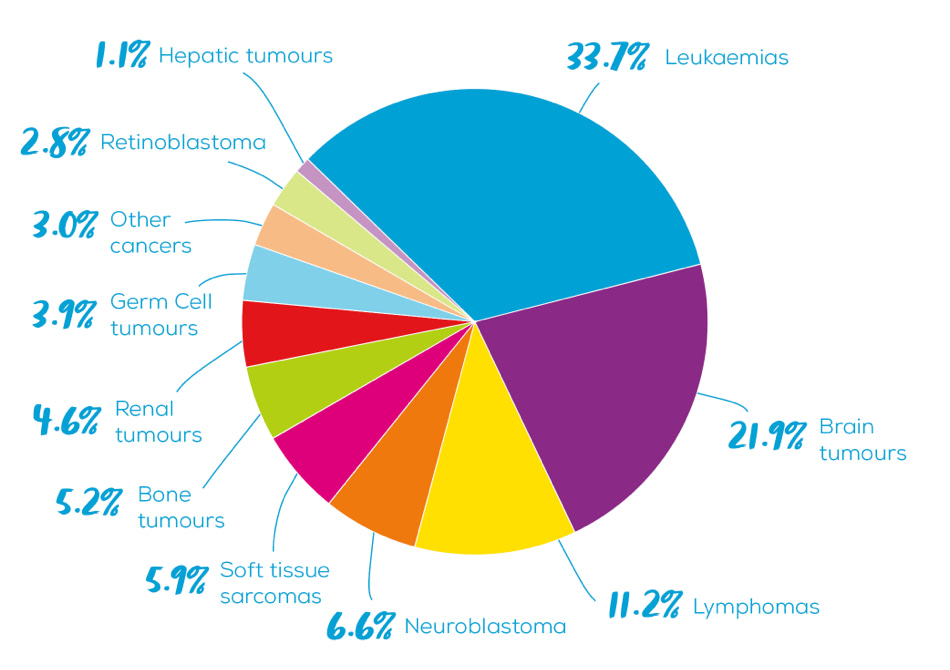

What types of cancer are affecting children in New Zealand?

An important part of recognising Childhood Cancer Awareness Month is helping Kiwis better understand different types of childhood cancer and how they impact on the lives of tamariki in Aotearoa.

There are many different types of cancer that affect children, some occurring more often than others. In the graph below, you can see the incidence rates of cancers diagnosed in children (0-14 years) in New Zealand between 2000-2019 by major diagnostic group. Source: National Child Cancer Network

Types of cancers we explain on this page are:

- Leukaemias

- Central Nervous System Tumours

- Lymphomas

- Neuroblastoma

- Rhabdomyosarcoma

- Wilms tumours

- Retinoblastoma

Leukaemias | loo-kee-mee-uhz

Leukaemia is the most common type of childhood cancer in Aotearoa, which is a group of cancers that develop in the bone marrow (the spongy tissue inside some of your bones) as a result of cancerous change in immature blood cells. No one knows exactly what causes leukaemia – most cases arise due to a spontaneous genetic mutation. In the 1960s, the five-year survival rate for children diagnosed with cancers in the leukaemia group was just 6%. Since then, many Kiwi children have participated in international collaborative clinical trials to test new methods of treatment. Great advances have been made, and the average five-year survival rate for cancers in the leukaemia group today is now close to 90%.

The most common type of leukaemia in children is acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL), named ‘acute’ because it progresses quickly and ‘lymphoblastic’ because of the excessive number of lymphoblasts (immature white blood cells) which crowd the bone marrow and enter the bloodstream. ALL occurs much more often in young children than in adults and makes up one quarter of all new child cancer cases. Children diagnosed with ALL undergo a particularly long course of treatment which usually lasts for just over two years. These children receive several cycles of multi-agent chemotherapy (where two or more drugs are used together), delivered according to strict protocols designed to target their cancer most effectively and minimise the amount of harmful side effects. Depending on disease factors and their initial response to treatment, some children also undergo biological therapy, radiation therapy, and stem cell or bone marrow transplantation.

Read Micaiah’s story to learn how his ALL diagnosis has impacted his family.

Central nervous system tumours

Brain and spinal tumours (otherwise known as Central Nervous System or CNS tumours) arise from different types of cells in these organs and are classified according to the cell type and area of the CNS in which they began. Most CNS tumours start in glial cells – the supporting cells of the brain. These tumours are known as gliomas and include astrocytomas, ependymomas and oligodendrogliomas.

Another group of tumours arise from embryonal cells. These tumours include medulloblastoma and ATRT (Atypical Teratoid/Rhabdoid Tumours). Altogether there are more than 100 different types of brain tumour, most of which are very rare.

CNS tumours as a group account for around 22% of all childhood cancers diagnosed in New Zealand, which makes it the second most common group of cancers affecting children in Aotearoa.

Tumours classified as low-grade are very slow growing and tend to remain in the part of the brain in which they started. High-grade brain tumours are likely to both be more aggressive in their behaviour and spread into the brain tissue which surrounds them. This can cause pressure and damage to the surrounding areas.

The treatment and likely outcome for a CNS tumour depends on a range of factors. Most CNS tumours require surgical removal, with many needing further treatment such as chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy. For these children, ongoing follow up is important as they can experience a range of long-term or ‘late’ effects from the tumour and treatment.

At present the five-year survival rate for CNS tumours is around 70% in New Zealand children. This is a significant improvement on the 1960s, when survival rates were closer to 30%.

Read Alex’s story on how his brain tumour diagnosis has affected his whānau.

Lymphomas | lim-foh-muhz

Lymphomas are the third most common type of cancer in New Zealand children. Lymphomas are a group of malignancies (cancerous growths) that start in immune system cells called lymphocytes. Typically, lymphomas develop in the lymph nodes or other lymph tissues, such as the spleen and tonsils. However, they can begin in almost any region of the body and spread widely similarly to other cancers. Common symptoms of lymphoma include weight loss, fever, tiredness and swollen lymph nodes. We don’t know why, but lymphomas are more common in boys than girls.

Based on the characteristics and appearance of the cancer cell, lymphomas are often divided into two groups; Hodgkin lymphoma and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Hodgkin lymphoma in children is similar to forms seen in adolescents and young adults but the types of non-Hodgkin lymphoma diagnosed in children are quite different to those seen in adults.

The specific type of lymphoma and the extent of its spread will determine the necessary treatment. Treatments may include chemotherapy, stem cell transplant, radiation therapy or surgery. Most children in New Zealand who are diagnosed with lymphoma will be treated according to a clinical trial or according to a disease-specific clinical protocol.

With current approaches, the vast majority of New Zealand children with lymphoma are cured of their disease.

Read Mya’s story to learn about the challenges that her Burkitt lymphoma diagnosis created for her family.

Neuroblastoma | new-row-blah-stoh-muh

Neuroblastoma is the fourth most common childhood cancer and accounts for one quarter of all cancers diagnosed in the first year of life. It can develop anywhere throughout the sympathetic nervous system, but most commonly originates in the adrenal glands on top of the kidneys.

Neuroblastoma belongs to a family of embryonal tumours which also includes cancers such as retinoblastoma, medulloblastoma and hepatoblastoma. These cancers are all caused by uncontrolled growth in precursor cells, known as blasts. We don’t yet know why blastomas develop but they are thought to be caused by genetic errors during early development.

Neuroblastoma is divided into low, intermediate, and high-risk groups based on factors such as the child’s age, how much the cancer has spread and genetic features. Those with low-risk neuroblastoma can often be cured by surgery alone and for some babies, close monitoring is all that is required. In contrast, those with high-risk disease are usually treated with a combination of therapies including intensive chemotherapy, surgery, radiation therapy, stem cell transplantation, biological-based therapy and antibody therapy.

New Zealand has participated in many international clinical trials for neuroblastoma. For those with low and intermediate risk disease, these trials have largely focused on reducing therapy while maintaining high survival rates. For those with high-risk disease, the focus has been on intensifying treatment to improve survival rates. Although the addition of antibody therapy a decade ago has significantly raised survival, high-risk neuroblastoma remains a difficult cancer to treat. Many survivors will have long-term effects due to their cancer treatment.

Read Caleb’s story to learn how his neuroblastoma diagnosis has impacted his whānau.

Rhabdomyosarcoma | rab-doh-myo-sar-coma

Rhabdomyosarcoma is a type of soft tissue sarcoma. Sarcomas start in mesenchymal cells, which are cells that normally develop into muscle, fibrous tissue, fat, blood vessels and other supporting tissues. Rhabdomyosarcomas most commonly develop in the abdomen, trunk, head and neck. A rhabdomyosarcoma diagnosis is incredibly rare; on average, only four children in New Zealand are diagnosed each year with this type of cancer. Most children diagnosed with rhabdomyosarcoma are under the age of five years old.

Like most childhood cancers, the cause of rhabdomyosarcoma is unknown. There is some evidence that children with rare genetic disorders such as Li-Fraumeni syndrome have a higher risk of developing rhabdomyosarcoma. The main types of treatment for soft tissue sarcomas such as rhabdomyosarcoma are chemotherapy, surgery and radiotherapy. Overall, the five-year survival rate for rhabdomyosarcoma in New Zealand is 66%, but this does vary widely depending on a number of clinical factors.

Read Nicole’s story to learn how a rhabdomyosarcoma diagnosis can impact whānau.

Wilms tumours | wilmz tyoo-muhz

Wilms tumours are a type of renal (kidney) tumour which is also known as nephroblastoma. Wilms tumours develop from embryonal cells, which are the cells responsible for organ development when a baby is still in the womb. Embryonal cells usually disappear before a child is born, but sometimes they don’t disappear and instead form clusters of primitive kidney cells called nephrogenic rests. During early childhood growth and development these nephrogenic rests can transform into Wilms tumours. Most Wilms tumours are diagnosed in children under the age of five years, and there are wide range of other associated clinical problems that may be seen and used as a clue to a genetic cause for the tumour.

Wilms tumours are usually treated by removing the kidney in an operation called a nephrectomy. Chemotherapy may be given before the nephrectomy surgery to reduce the size of the Wilms tumour and also after surgery to prevent the tumour coming back. Radiotherapy may also be required.

The five-year survival rate for Wilms tumour in New Zealand is 96%. Very few children have long-term kidney problems after Wilms tumour treatment, but most children will have regular check-ups to look for any recurrence or other issues with their health. Rarely, the tumour can develop in both kidneys, and treatment is aimed at preserving kidney function and as much kidney tissue as possible to avoid the need for long-term dialysis and ultimately a kidney transplant.

Read Brianna’s story to find out what living with a Wilm’s tumour is like.

Retinoblastoma | reh-ti-no-bla-stow-muh

Retinoblastoma is a type of eye cancer which is most common in children under the age of five. In many cases (40%), retinoblastoma is caused by a mutation of the RB1 gene, which is inherited. However, some retinoblastomas are not passed on in the family and occur because of gene mutations which occur at an early stage of development in the womb and retina development.

Retinoblastomas are staged according to whether the tumour is confined to the retina (the thin layer of cells at the back of the eyeball that detect light) or has spread to other tissues within or even outside of the eye. Knowing the stage and spread of the retinoblastoma helps doctors decide on the most appropriate treatment. The most common treatments for retinoblastoma are:

- Cryotherapy, a type of treatment which involves the tumours being frozen away.

- Laser therapy (photocoagulation or thermotherapy), a type of treatment which involves a laser beam being used to heat the tumour and break it down.

- Removal of the eye (enucleation) is often required to control the disease.

- Chemotherapy is used for those tumours that have spread beyond the retina.

Retinoblastoma has the best survival rates of all childhood cancers, with a 100% five-year survival rate in New Zealand. Following treatment, a child with retinoblastoma will be monitored over time to make sure no new tumours develop. Genetic counselling is available for children and their families who have heritable retinoblastoma and the associated RB1 gene mutation.

Read Jaxon’s story to learn more about retinoblastoma and how it can affect Kiwi families.

Every dollar counts

The difference you’ll make

To ensure each family living through childhood cancer in New Zealand receives the support they need, we need to raise at least $7 million each year – and we receive no funding from the government. That means we rely on the compassion and generosity of Kiwis like you.

Every donation, no matter how big or small, makes a real difference for tamariki with cancer and their whānau. Here are some examples of how your contribution could help.